Mediæval Knights

Medieval Knights were armed and mounted warriors who fought for Lords during the medieval period and usually came from wealthy families, they had an important place in medieval society which followed class rules dictated by the Feudal system

Medieval Knights were the armoured warriors of medieval times who fought on horse-back, they usually trained from an early age of around 7 years until they were in their early twenties. When they had mastered all the skills needed they were knighted in a dubbing ceremony.

Due to the costs involved in training to become a Medieval Knight and the dedication involved, it was deemed to be of high honour to be a knight in medieval society. The title of Knighthood was tied in with the status of nobility and basically meant that you were a trained nobleman that was ready to serve a Lord or king in battle.

Becoming a knight was a long and difficult process and only the sons of Nobles could become Medieval Knights. Training to be a medieval knight started at a very early age around seven years of age boys would become a page and would start to learn how to fight and ride a horse in a castle until they were around 14 years of age, then they would become Squires.

During the early years of becoming a knight pages were given a basic education and taught how to handle themselves in everyday life doing chores such as serving food at the table, it wasn’t until they became Squires and were sent to live with a Lord that training to become a knight began in earnest.

A page would become a squire at the age of fourteen; he would then become an understudy to an established medieval knight. This was his apprenticeship that would eventually lead to him becoming a knight and he would look after his mentor doing a variety of task whilst observing and learning new skills from his master.

A squire had to master a variety of weapons whilst being an expert on a horse; he needed to know everything it took to become a medieval Knight. The apprenticeship was long and hard and the squire would have to keep his master’s armour and weaponry in top condition. Squires had to learn fighting techniques and riding skills and would watch their masters closely and follow them into battle.

Medieval knights needed to be extremely strong to be able to carry heavy weapons during long battles whilst wearing heavy armour. Squires worked on their strength and conditioning on a daily basis and were extremely fit. Squires needed to practice their fighting skills and learn different fighting techniques with different weapons on their way to becoming a knight. As the medieval period progressed, training methods advanced and specialist equipment such as the Quintain introduced.

The Quintain was a rotating pole that squires and knights charged on horseback, they would try to hit the shield cleanly with the tip of their lance and if they did not hit the shield at the right place at the correct speed the rotating sandbag could knock them from their horses.

Medieval Squires would practice acrobatics and do other strength and fitness training on their route to becoming a knight. Squires would take part in mock sword fights using wooden, whalebone swords called batons to hone their swordsmanship and improve their fitness. Small round Buckler style shields made from wood or metal used to defend against attacks.

Medieval Squires had to learn the code of chivalry that applied to all squires hoping to become a knight; this was basically rules the Medieval Knights had to follow and involved morality teachings, codes of acceptable conduct that knights had to display towards people especially women and strict rules they had to obey.

After years of intensive training under the wing of an established knight it would finally be time for the medieval squire to make the transition to becoming a fully-fledged knight, this would usually be around 21 years of age. In preparation for the special dubbing ceremony the following day, squires would spend the night before the ceremony in prayer asking for guidance in their new role as a knight.

The dubbing ceremony was a big event often followed by feasting and dancing, sometimes tournaments took afterwards.

A knight or even a king could perform the dubbing ritual but often the squire’s proud father that would perform this duty.

The squire dressed in a white robe would kneel down and have both his shoulders tapped with a sword, usually by his father as other nobles watched.

A squire was given a sword and spurs for his achievement and new found status at becoming a medieval knight. At the end of the dubbing ceremony, a knight’s father would say the following or similar words:

“Go fair son be thou a valiant knight and courageous in the face of your enemy and be true and upright that God may love thee".

If a battle was about to commence the dubbing ceremony could be brought forward as a new knight would be eager to prove his worth on the battlefield and becoming a knight would inspire them in battle. On rare occasions, a squire would become a knight on the battlefield if they had carried out an act deemed worthy of such accolade.

Interesting Facts:

§ A page would become a squire and a squire would become a knight

§ Training to become a knight started at the early age of around seven years old

§ Squires were typically knighted and proclaimed knights at around 21 years of age

§ Only noble boys from wealthy families could become knights

§ Squires had to carry out the fitness and strength exercises to become a knight

§ Squires would practice hitting rotating shield targets called a Quintain to hone their skills

§ Wooden batons were used to practice close combat sword fights

§ Squires practised acrobatics to improve their strength

§ A Quintain was used for training to use the lance and horsemanship

§ A squire would become a knight in a dubbing ceremony

§ Squires received a sword and their spurs on becoming a knight

§ The dubbing ceremony was followed by feasting and dancing

§ Squires would wear white robes to dubbing ceremonies

§ A squire could become a knight on the battlefield

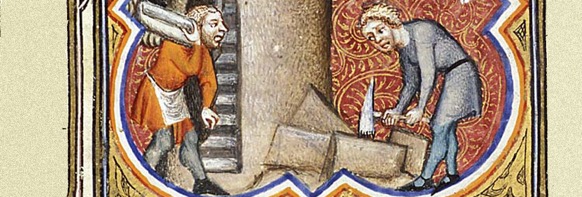

The Knaves

The Bilingual Thesaurus of Medieval England lists three words for kitchen servants that were used in England between 1100 and 1400. Two of them (‘knave’ and ‘quistroun’) are from Middle English and one (‘cuistron’) is from Anglo Norman, or Anglo French as it is sometimes referred to, the variety of French spoken in England after the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The Middle English word ‘knave’ comes from Old English ‘cnafa’ (possibly derived from the Mercian word ‘cneafa’).There are various recorded references to the word ‘knave’ to describe a kitchen boy/cook’s servant or scullion in Middle English, the earliest being from Ancrene Riwle, dating from around 1230:

‘Beon bliðe iheortet ȝef ȝe þolieð danger of sluri, þe cokes cneaue [Tit: cnaue; Nero: knaue], þe wescheð & wipeð disches i cuchene’. Ancr. (Corp-C 402), 192/3.

The latest citation we have in the Middle English Dictionary is from around 1500, from a text called Octavian:

‘The kokes knaue, þat turneþ þe spyte, Upon þy wyf he hath begete On of þo two’. Octav (2) (Clg A.2).

‘Knave’ was a widely used word that had wide applications. In addition to kitchen servants it could be used to refer to male infants, peasants or labourers, and crucially, wastrels, or good for nothing rogues.

The following two quotes, from Cleanness by the Pearl Poet and Lydgate, illustrates this well:

‘He wonded no woþe of wekked knavez..For harlotez wyth his hendelayk he hoped to chast’. Cleaness IMEV 635; Manual 2.II.4.

‘And so thestat of politik puissaunce Is lost wher-euer knaues haue gouernaunce’. Lydgate FP (Bod 263).

So, like ‘scullion’, ‘knave’ could be used as an insult. However, the two uses of the ‘knave’ seem to be more differentiated than the two uses of ‘scullion’, which appear to overlap more, possibly because of the heavily stratified nature of medieval and early modern society. In other words, calling someone a scullion was insulting because the meaning of ‘scullion’ became extended, from someone who performs menial jobs in a kitchen to someone who is, as the OED definition of ‘scullion’ has it, ‘a person of the lowest order’. Whereas, to call someone a knave, in a pejorative sense, was to imply that they were dishonest, unprincipled, cunning, unscrupulous; even a villain. So although you could refer to a ‘cook’s knave’, when ‘knave’ was used as an insult, it arguably carried a much stronger pejorative sense than ‘scullion’.

Middle English ‘quistroun’ and Anglo Norman ‘cuistron’, are actually the same word, in that the English word was borrowed into the lexicon from French. The Middle English Dictionary suggests that the primary meaning of ‘quistroun’ was ‘a cook’s assistant or errand boy, scullion’. It could also be used to refer to: ‘a page, lowly servant, knave; also, a sutler, camp follower;’. The quote below from Octavian illustrates the culinary usage:

‘Sche segth a boy, loþly of face, A quysteroun..And seyde, ‘Hark, þou cokes knaue.’ Octav. (2) (Clg A.2). 154

The Anglo Norman equivalent ‘cuistron’ is also defined as a scullion or a cook’s boy in the Anglo Norman Dictionary, and various quotes illustrate this usage, such as the following quotes from Gaimar and Bibb Roth (G):

‘Sa niece mesmariee ad; Il la dunad a un garçon Ki Cuaran aveit a nun; […] Cil Cuaran esteit quistrun Mes mult esteit bel vadletun’ Gaimar 103

‘Va t’en, quistroun, ou toun havez (M.E. fleyshhock) Estrere le hagis del postnez’ Bibb Roth (G) 1035

Again, this word doubled up as an insult, in both languages. In French, there is the following quote about ‘bastard cuistrons’, from the Dictionnaire du Moyen Français (1330-1500):

Cuistron bastard. “Vil bâtard” : Questron bastard, je te occiray (Precef. IV, R., 608).

Meanwhile, in English, there is a reference to the ‘foulest quisteroun’ in Ywain:

‘I sal hir gif to warisowne, And of þe foulest quisteroun, Þat ever ȝit ete any brede, He sal have hir maydenhede’. Ywain (Glb E.9) 2400

And a glowing description of the beautiful God of Love, who was ‘lyk no knave, ne quystroun’ in the Romance of the Rose:

‘This God of Love of his fasoun Was lyk no knave, ne quystroun; His beaute gretly was to pryse’. RRose (Htrn 409) 886

What’s more, these insults were not just reserved for people, or used for the purposes of comparison in relation to gods. There are two quotes in the Middle English Dictionary that refer to the ‘whel of quistrounes’, which was a contemptuous epithet for the wheel of Fortune:

‘So þe qwele of qwistounes [read: qwistrounes] ȝoure qualite encreses, Þat noþir gesse ȝe gouernour no god bot ȝour-selfe!’ Wars Alex (Ashm 44) 4660

This last quote suggests that the pejorative sense of Middle English ‘quistroun’ was relatively established and well known, at least by the later medieval period, which is when the text it is taken from was written.

So it is clear that before ‘scullion’ came along in the sixteenth century, there were already words for kitchen servants in both Middle English and Anglo French that doubled up as insults.

© 2018 – ASTOLAT PRODUCTIONS

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: JMCAMILLERI