Vikings and Sagas

“ And then there were these Northmen with their vision of greatness. They dreamed a world outside their walls, a land of gold so rich, so prosperous, more generous than the cold dark fjords. And off they went in their quest, together with their lore, and though somewhat they meandered, they reached our lands and our times.” [J.M.Camilleri]

The Vikings

The Old Europe, the one that survived after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, had settled into a relative peace and a routine known to all. Britain too, with its factions and reigns, seemed to hold ground. But, then, Britain was the first to taste the assault of Vikings. Until then peaceful people, Scandinavians went to the assault of Europe from the end of the eighth century. The first victims were the English. The 8th June 793, the small town of Lindisfarne, Northumbria is attacked by the Northmen. Never before such terror had appeared in Britain as these pagans shed the blood of saints and men of God on the altar, desecrating them in the temple of God, throwing them like rubbish in the streets.

From the end of the 8th century to the 1000s, the Viking phenomenon marked the spirits. Scandinavians crossed the sea and invaded northern Europe, from Iceland to Russia. Some settled on the banks of the Seine, in a region called "Normandy". The motives behind such show of force are still not really known today. What reasons led them to take off? Historians still debate the subject, but we can already discard some unconvincing hypotheses, such as the hatred of Christianity or the overpopulation of Scandinavia, though the extensive and thorough pillaging of churches and villages and cities indicate that this plunder was a quest for riches more than glory.

So, after all, were these Viking raids some form of revenge? In the year 841, after ravaging Rouen, a Viking fleet descended the Seine. On the banks of the river, the silhouette of Jumièges emerged, attracting far too much the attention of the band. It was a total tragedy. The monastery was burned and pillaged. There was that awful sense of helplessness. Little wonder for everyone knew how much the Northern men were happy to attack churches and to mistreat monks and other clerics. From there to think that the motivation of the invaders rests on a hatred of Christianity, there is only one step that more than one historian has unfortunately crossed.

Generally, these authors accuse Charlemagne. A few decades earlier, the Frankish emperor had made a name for himself in Saxony, a region bordering Denmark, by a policy of forced Christianisation. The choice for the Saxon pagans was to either convert or to die. There was no other option. Forced conversion against personal principles and beliefs led to a general sense of discomfort. There is no doubt that these brutal methods have left their mark and some resentment against the Franks and the cross, yet this was not the prime motive otherwise Viking raids would be just a story of revenge. In the end, the explanation is appropriate for the Saxons and their Danish neighbours who welcomed the oppressed but it does not hold for the other Scandinavians (Norwegians and Swedes) that the Baltic Sea isolated and thus, preserved Charlemagne's enterprises and forced Christianisation. For at least these two peoples, the cause was another.

In most televised scenarios, the viewer discovers hordes of “”savages” living in the Far North. Their dream is simply to build strong ships to cross the gigantic wall of ice that separates them from the richer and warmer regions of the Western continent.

This is the common place story in the collective of many, coming from a historical literature and, recently, in fantasy literature. These northern regions generally shelter vigorous peoples whose overflow is about to sweep over the southern kingdoms. The Vikings, prisoners of the cold Scandinavian peninsula, would agree well with this shot. Could overpopulation and the search for more lenient lands not explain their expansion across Europe?

Once more, this is not a credible option. There are sociological and anthropological theories to substantiate otherwise. If we were to go back to the example of the savages, they live in an arctic landscape where nothing grows. Although writers state otherwise in their fantastic make-believe stories, it is impossible to imagine a large population in these environmental conditions. It is the same story for the Vikings. Scandinavia offers a terrain too rugged and a climate too rough to consider population pressure. Similarly, we can doubt the climatic tropism of the Vikings. We have to remember that they colonised Iceland and Greenland, two very cold islands. Therefore, I would suggest that the seeking of other lands was survival. As is always the case, other lands are often inhabited and whoever arrives after is an intruder. War, pillaging, plunder and massacres are a consequences of getting with might what one believes is one’s right.

There was a great thirst for riches and money. The Vikings who left the burned monastery of Jumièges approached Fontenelle the very next day, another rich abbey in the Seine Valley. The scenario here changed. This time there were no flames because the monks paid the menacing warriors to save the buildings. This became the common method of mediation in order to save a culture and to preserve a heritage. It became a real way of negotiating. A few days later, a religious delegation comes to meet the invaders. They are monks of the abbey of Saint-Denis. The Scandinavians do not kill them. They do not see any interest in it. The brothers negotiate a ransom for the release of sixty-eight prisoners. A very hefty ransom is paid. Once the coins are on board, the drakkars abandon their prisoners and leave the Seine. These two examples prove that making money interested the Vikings more than smashing skulls. Theirs was a new way of financing new ships and armaments to go ahead with their ideas of expansion, of settling in other lands and leaving their mark on the social makeup of mediæval Europe.

In this quest for wealth, the Vikings show great inventiveness. Looting churches (they have the advantage of sheltering treasures without being defended), the capture of humans to sell them as slaves, obtaining huge sums of ransom for the most important characters, the paying of tribute, getting engaged as mercenaries in the private squabbles and battles of small kingdoms and, add trade to this list because these terrible Vikings were capable also of hanging up their axes and their armour and work peacefully with Europeans.

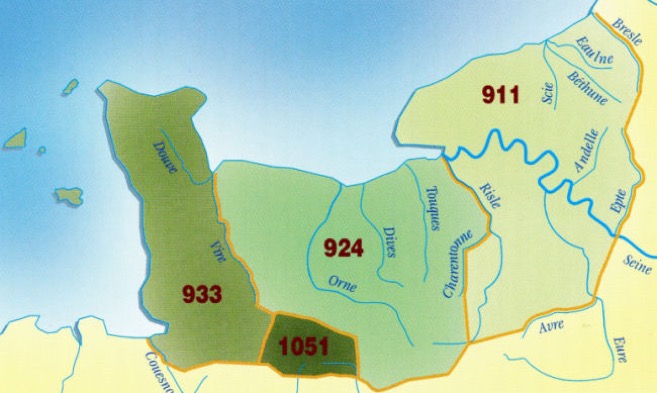

When the Viking leader Rollo moved to Normandy at the end of the 9th century, he was surely fortunate after a career rich in migration and robbery. So, one would ask, why was he still fighting? What was he missing? He was simply missing a title that would put him at par with the others, his “peers”. Charles the Simple, the king of the Franks, understood this quite well, so much so that he abandoned a part of his kingdom, what was to become today’s Normandy and Rollo became the Count of Rouen. Rollo could now share with his men not only loot but he was able to give them something more permanent, a land where to settle and which they could call home.

In 911 the French King, Charles the Simple, met with the Viking chieftain, Rollo at Saint-Clair-sur-Epte in order to sign a treaty, permitting the Vikings to settle in Normandy in return for their protection of the French Kingdom from the invasions of other Northmen (as the Vikings were called by the French). For a long time it was believed that the only existing source was a long and perhaps a bit farfetched description of the meeting and the negotiations in the French Cronicle of Dudo of St. Quentin. Hence historians have from time to time considered the treaty a myth. However, there does exist a document from 918, in which we are told that the king donate some land to the abbey of St. Germain-de Prés, except that part which

“praeter partem ipsius abbatiae quam animus Normannis Sequanensibus,

uidelicet Rolloni suisque comities, pro tutelar regni.”(*)

(*) [we have granted to the Northmen at the Seine, that is to say Rollo and his companions, in order for them to safeguard the kingdom.]

The Sagas

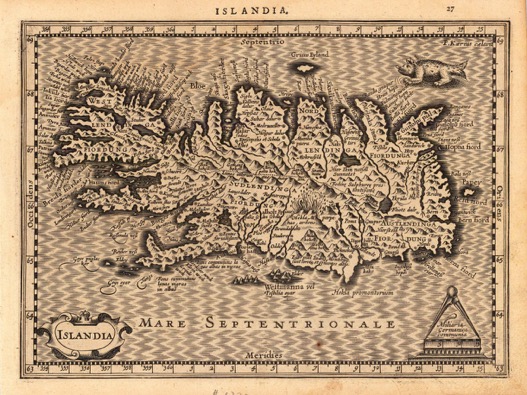

Recent research revealed that in Iceland more books are written, published and sold per person per year than anywhere else on the planet. I have known for quite some time, partly because of my travels and partly because of my Icelandic friends, that the average Icelander reads four books per year. They also are budding writers. One in ten will publish something in their lifetime. The reasons for this are manifold.

With this in mind, I would like to explore with you how the Viking Sagas came into being. The long and dark winter nights offered the time and the atmosphere to create. The Icelanders were, by far, the most literate of the Northmen. There was a rough geographical expansiveness that made other entertainment too difficult. The weather itself was not kind, the climate cold and harsh and the terrain rugged and uneven. The population was small. Iceland had been, after all, colonised by the Vikings themselves. They integrated with the indigenous population and, struck by their literacy and their innate ability to write, Vikings and Norsemen kept some Icelanders with them to put down in writing their feats and their stories and to record their passage in history for posterity. For this reason we can safely conclude that Iceland's most famous literary exports were The Sagas.

The Sagas remain an intrinsic part of Icelanders' identity to this day and their presence around the country is unavoidable. Here unfolds the change of time in history. The Sagas become physical documents which trace the lives of the indigenous Icelander people during a most tumultuous era when the Vikings were changing the shape of society across Northern Europe and Christianity, Catholicism and Paganism were all fighting it out to be the prevailing belief system. With events of great proportion taking place during the tenth and eleventh centuries, the Sagas have a lot to recount in terms of history and literature. The identity of the authors roughly places itself at circa 1190 -1320. I venture add that this collection of stories is one the most important European works of the past thousand years. It places itself at par with Chaucer’s colourful “Canterbury Tales” and Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. The Sagas are as exciting as is “Beowulf” and epic in their nature as the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” and even more interesting to read than other writings of the period. The Sagas contain beautiful passages and descriptions, striking observations and pathos in certain parts, all those strings that pull at our emotions. They also contain some remarkable and monumental events, above all that of the Norse explorer Leif Ericsson whose journey leads to the discovery of a large island he called Vinland and which was later divided into two and renamed Canada and America.

The Sagas are the precursors of modern writing and their style still influences the way we tell and read stories today. Homer's tales are fantastical works that concern mythical creatures, Gods and unbelievable reckonings, the most improbable of events happen only though the intervention of one god or another and man is seen manipulated by this fate. Though trolls and ghosts feature quite often in The Sagas, much of this collection of stories remains grounded in reality. The Sagas tell stories of farmers, families and fighters, lovers, warriors and kings. As is normal with human behaviour, they speak of betrayal and dilemmas which are, for the most part, believable and credible. Women play a strong role too. They have an important role in their society. They are mothers, lovers, fighters, policy makers too. Few characters are as memorable as Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir (Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir), believed to be the first person of European ancestry to be born in America, with a formidable character, a great explorer and resilient, who went through the passages of her time, converting to Christianity, going on pilgrimage to Rome and, in her final years, retiring in hermitage.

The style in which The Sagas are written is, like some of today's best fiction, unpretentious and unadorned. Characters move from one point to another with their drakkars and their long-boats. The narrators remain unemotional, detached and impartial; people live and die without too much sentimentality or judgement involved. It is the reader who adorns the Sagas with all that. Across a variety of autonomous stories, the early authors of the Sagas deliver complex and multi-generational tales in a tone that, despite being born out of a very different philosophical age, makes them surprisingly relevant and readable at a distance of a millennium. Strikingly, the Sagas created an appetite for a certain type of literature that is evident today in biographies, modern day sagas (aga-sagas), the works of Tolkien, Pratchett and others, and this because, ultimately, they make great reading.

The Norse Myths are about the places and people across Scandinavia (as well as the Norse Gods Odin, Thor, Loki, Freya, etc.) and yet, the majority, if not all, of the sagas, myths and legends were written in Iceland. As stated earlier, Iceland has a 99% literacy rate today, but it has always been one of the most literate and educated countries in the world, even in the Viking days. It is a little known fact that, though any Norse Mythology professor or Icelander could confirm it for you, other countries would often send for and keep an Icelander around as a historian and a writer; the Norwegian Kings would often have one to keep track of his noble deeds and record them in writing. The man who was able to write and read was held in awe.

While they were written in Iceland, many of the sagas did not originate there; as previously stated, they were mostly about the heroes of other countries. The ones that were set in Iceland, however, were often different from the standard semi-divine heroes and gods of the other countries. Some of the most famous Icelandic Sagas, such as Egil’s Saga and Njal’s Saga, were written about everyday people, such as farmers and lawyers who did great and noble things, hence demonstrating to everyone that the real nobility was that of the heart. This is not to say that the Icelanders did not have stories of or believe in the Norse Gods. There is historical evidence that they did, but these sagas show us that Icelanders placed significant value in the practice of the law, and in everyday people doing the things that matter. They also show the Icelanders attempting to move from a more primal way of vengeance and violence to a time of peace through the practice of law and friendship. This is, more or less, what happens in Europe, more so after the establishment of the Northmen in Normandy, France and with other great conquests such as that of William I in 1066 in Britain and the intermittent but equally important establishment of the Normans in the Mediterranean between 1061 and 1091.

© 2018 – ASTOLAT PRODUCTIONS

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: JMCAMILLERI